Chemical Nomenclature

I. The reason that we care about naming compounds

a. Naming, a.k.a. “nomenclature” of compounds

b. Significance: must know what we are talking about very clearly when we refer to substances by their names of formulas.

c. For instance, what is “carbon oxide”? There are two different formulas for a carbon-oxygen compound, both of which obey the octet rule, CO and CO2. Which one is “carbon oxide”? Answer: neither. One is carbon monoxide, the other is carbon dioxide.

d. When we say sodium chloride, what is the formula? This is easy, because we know that Na forms 1+ ions, and Cl will usually form 1- ions. Thus, NaCl.

e. When we say “iron chloride,” what is this compound’s formula? Well, iron is a transition metal, and it turns out that iron can form Fe2+ ions, but can also form Fe3+ ions.

i. Fe – [Ar]4s23d6 -- can lose two electrons from the 4s to become simply [Ar]3d6, which is the electron configuration for Fe2+.

ii. Alternatively, Fe can become stable by losing both 4s electrons and one form the 3d, leaving it with a rather stable half-filled d sublevel. Fe3+ has an electron configuration of [Ar]3d5.

iii. Transition metals often become stable by obtaining a pseudo noble gas configuration. That is, they do not attain a full highest-occupied energy level in their outer shells (i.e., do not attain complete octets). Instead, they attain full or half-full sublevels.

f. So, “iron chloride” could be FeCl2 or FeCl3. We need to have a way of distinguishing these compounds from one another. As it turns out, FeCl2 is called iron (II) chloride and the FeCl3 is iron (III) chloride.

II. The goals of this chapter:

a. You should be able to name a compound, given its chemical formula. Example: N2O4 is dinitrogen tetroxide.

b. You should be able to write the chemical formula for a compound if you are given the name of that compound. Example: manganese (IV) oxide is MnO2.

c. We will only concern ourselves with simple ionic and covalent (i.e., molecular) compounds. (It is a rare chemist who can name any compound under the sun – organic compounds, proteins, organometallic compounds, steroids, etc. – without reviewing at least the rules for that particular class of compounds first.)

Examples of compounds that you will NOT have to name! J

An example of an amino acid.

An example of an amino acid.

A propellane, an

example of an aromatic compound.

A propellane, an

example of an aromatic compound.

A hexose, which is an example of a

carbohydrate.

A hexose, which is an example of a

carbohydrate.

An example of a porphyrin.

An example of a porphyrin.

III. Naming binary ionic compounds

a. Situations in which there is not a “special metal”

i. If the metal involved always forms the same charge, then there is no need to specify its charge in the compound’s name. Examples: all group I and group II metals, aluminum, Zn, Ag, Cd. Zn always forms Zn2+, Ag always forms Ag+, Cd always froms Cd2+.

ii. The anion takes an –ide ending.

iii. Examples:

1. NaCl is sodium chloride

2. CaCl2 is calcium chloride

3. AlCl3 is aluminum chloride

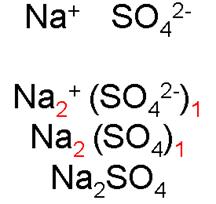

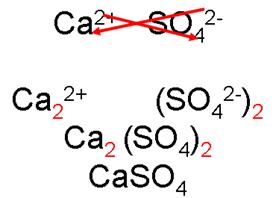

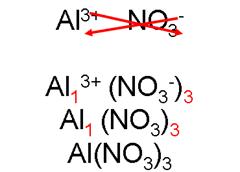

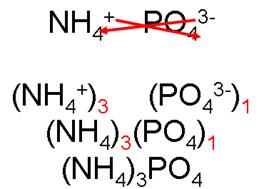

b. Writing formulas for the above compounds

i. Write down the ions, cross over the charges.

ii. “Cancel” these subscripts, if necessary, just as you would a fraction.

__________________________________________________

sodium chloride

calcium chloride

calcium phosphide

c. Situations in which there is a “special metal”, i.e., the metal is a transition metal or a group 14 metal.

i. The bad news about these metals is that it is very difficult for a 1st year chemistry student to figure out how a transition metal forms an ion.

ii. For instance, iron (Fe) has the electron configuration [Ar]4s23d6. It will not lose 8 electrons to gain the electron configuration of the noble gas Ar. Because it is a metal, it certainly will not gain electrons, and at any rate it would have to gain 10 electrons to have the full octet of Kr.

iii. Instead, transition metals and group 14 metals will attain a pseudo noble gas configuration, in which the metals become stable ions by losing enough electrons to be left with either a full sublevel, or a half-filled sublevel. Full sublevels and half-filled sublevels are stable, though not nearly as stable as filled highest-occupied energy levels (i.e., filled valence shells).

iv. These metals usually have more than one possible ion that they can form.

v. Fe will lose either two electrons to become Fe2+ as [Ar]4s13d5, or it will lose three electrons to become Fe3+ as [Ar]4s03d5.

vi. Ions you should be able to recognize and look up on a table are listed below.

|

Common Metal Ions |

||

|

Ion |

Systematic Name |

Common Name |

|

Fe2+ |

iron (II) |

ferrous |

|

Fe3+ |

iron (III) |

ferric |

|

Cu+ |

copper (I) |

cuprous |

|

Cu2+ |

copper (II) |

cupric |

|

Pb2+ |

lead (II) |

plumbous |

|

Pb4+ |

lead (IV) |

plumbic |

|

Cr2+ |

chromous |

|

|

Cr3+ |

chromium (III) |

chromic |

|

Sn2+ |

tin (II) |

stannous |

|

Sn4+ |

tin (IV) |

stannic |

|

Co2+ |

cobalt (II) |

cobaltous |

|

Co3+ |

cobalt (III) |

cobaltic |

|

Hg22+ |

mercury (I) |

mercurous |

|

Hg2+ |

mercury (II) |

mercuric |

** ALWAYS: Zn2+, Ag+, Cd2+ **

vii. The stock system uses roman numerals in parentheses to indicate the type of ion in the compound. Example: FeCl2 is iron (II) chloride, FeCl3 is iron (III) chloride. You are responsible only for the stock system of naming compounds containing these “special metal” ions.

viii. The classical system of naming uses the “-ous” and “-ic” prefixes to indicate the lower and higher charges, respectively. Example: iron (II) chloride is ferrous chloride and iron (III) chloride is ferric chloride. You are not responsible for using or recognizing the classical nomenclature system, though it will be helpful in the lab, understanding chemical names on packaging, etc.

d. Writing formulas for compounds that contain polyatomic ions.

i. The polyatomic ions that you should recognize, but which you do not need to memorize:

ii. Notice that ions formed from nonmetals take the” –ide” ending. Usually, the converse is true: “ide” ions are formed from nonmetals. Notable exceptions: cyanide (CN-) and hydroxide (OH-).

iii. These examples are similar to the examples using monatomic (one-atom ions).

sodium

sulfate

______________________________

calcium

sulfate

_______________________________

aluminum nitrate

_____________________________

ammonium phosphate

IV. Naming covalent compounds (a.k.a. molecular compounds)

a. Remember, covalent bonds are formed between nonmetals and nonmetals

b. We will only name binary molecular compounds. Binary molecular compounds only contain two different elements.

c. Consider these two compounds that can be formed from carbon and oxygen: CO and CO2.

d. Using the word “carbon oxide” would not be sufficient, because tere are two different forms of “carbon oxide.”

e. Because carbon is not an ion in these compounds, it does not have a charge. That is one way to rationalize to yourself why we do not use the charge on carbon in parentheses (as we do when naming transition metal-containing ionic compounds).

f. For covalent compounds, we use prefixes to indicate the number of each atom in a compound.

i. The first word in the name gets no suffix, but the second word in the name gets the “ide” suffix, similar to how we write names for binary ionic compounds.

ii. Never use “mono” if there is one atom of the first element. Ex: carbon dioxide = CO2, not “monocarbon dioxide.”

iii. DO use the appropriate prefix to indicate the number of atoms of the first element if there IS more than one atom of that element. Example: P2O5 is diphosphorus pentoxide.

iv. The suffixes are shown below.

|

Prefixes Used in Naming Binary Molecular Compounds |

|

|

Prefix |

Number |

|

mono |

1 |

|

di |

2 |

|

tri |

3 |

|

tetra |

4 |

|

penta |

5 |

|

hexa |

6 |

|

hepta |

7 |

|

octa |

8 |

|

nona |

9 |

|

deca |

10 |

V. Naming acids

a. For our purposes, for right now, acids are compounds that start with one or more “H’s” and end with some anion. “HX”, H2A”, “H3D”, etc., where X-, A2-, and D3- are anions attached to one or more hydrogens.

b. We will consider three cases of acids:

i. Acids which contain an anion that ends with “-ide”

ii. Acids which contain an anion that ends with “-ite”

iii. Acids which contain an anion that ends with “-ate”

c. Acids which contain an anion that ends with “-ide”

i. Examples of ions that end in “ide”: cyanide, chloride, bromide, iodide, sulfide.

ii. First, chop off the suffix “ide”

iii. Then, add the prefix “hydro”, wite the stem, then add the suffix “-ic acid”

iv. HCN

1. “hydrogen cyanide”

2. Cyanide

3. Cyan-

4. Hydrocyanic acid

v. HCl

1. “hydrogen chloride”

2. Chloride

3. Chlor-

4. Hydrochloric acid

vi. HBr

1. “hydrogen bromide”

2. Bromide

3. Brom-

4. Hydrobromic acid

vii. HI

1. “hydrogen iodide”

2. Iodide

3. Iod-

4. Hydroiodic acid

viii. H2S

1. “hydrogen sulfide”

2. Sulfide

3. Sulf-

4. Hydrosulfuric acid

5. Note the weird stem change. Same thing happens with “phoshide”

d. Acids that contain an anion that ends with “-ite”

i. Examples: sulfite, chlorite, nitrite, hypochlorite.

ii. First chop off the suffix “ite.

iii. Next, write down the stem plus the suffix “- ous acid”

iv. H2SO3

1. “hydrogen sulfite”

2. Sulf-

3. Sulfurous acid

4. Note the weird stem change. Similar thing happens with phoshphite ion.

v. HClO2

1. “hydrogen chlorite”

2. Chlor-

3. Chlorous acid

vi. HNO2

1. “hydrogen nitrite”

2. Nitr-

3. Ntrous acid

vii. HClO

1. “hydrogen hypochlorite”

2. Hypochlor-

3. Hypochlorous acid

e. Acids that contain an anion that ends with “ate”

i. Examples: chromate, dichromate, nitrate, sulfate

ii. First, chop off the suffix “-ate”

iii. Then, write down the stem + “ic acid”

iv. H2CrO4

1. “hydrogen chromate”

2. Chrom-

3. Chromic acid

v. H2Cr2O7

1. “hydrogen dichromate”

2. Dichrom- (note that “di” is actually a part of the dichromate ion’s name and is therefore not omitted

3. Dichromic acid

vi. HNO3

1. “hydrogen nitrate”

2. Nitr-

3. Nitric acid

vii. H2SO4

1. “hydrogen sulfate”

2. Sulf-

3. Sulfuric acid. Note the weird stem change. Same thing happens with phosphoric acid (from phosphate ion)

|

Rules For Naming Acids |

|||

|

Anion ending |

Example |

Acid name |

Example |

|

-ide |

Cl- chloride |

hydro–(stem)–ic acid |

hydrochloric acid |

|

-ite |

|

(stem)–ous acid |

sulfurous acid |

|

-ate |

|

(stem)-ic acid |

nitric acid |